“[T]oday’s viewers get their history lessons from movies and biopics, not textbooks. And that’s where writers can a assume a greater role in the “truths” they portray.”

February 28, 2022 By Alan A. Winter

Crime! Mystery! Suspense! Oh, my! If this were Oz, crime/mystery/suspense writers would have paved the yellow brick road with vivid descriptions bathed in subtleties; they would have released clues as needed to move the story forward; they would have built in a side path or two that led to a blind alley; and, in the end, they would have lifted the curtain to reveal the Wizard hiding in Emerald City. Pulling back that curtain exposed hidden truths in L. Frank Baum’s story. Yes, truths! Oh, my!

Packaged in many ways, truth is the backbone of every story that satisfies the reader, no matter if we write murder mysteries, thrillers with its many subgroups, historical suspense, or real-life crime novels. Truth can be the meticulous historical accuracy Ken Follett artfully portrayed in Pillars of the Earth. While Kingsbridge is fictional, we see, smell, and hear the sights how Follett builds the cathedral and the town around it, stone-by-stone, house-by-house, event-by-event. We are transported to that time to “live” in the book, to feel the tensions that run through it because we care about the characters. Likewise, we find an authenticity in Umberto Ecco’s The Name of the Rose. Ecco immerses us in details and minutiae that give the book its air of verisimilitude. We believe it. We transfer “truths” to the story that may not have existed but were earned by its masterful descriptions. We care not that . . . Rose is not historically accurate.

What can be said about Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code? Or Caleb Carr’s The Alienist? Neither story is real. In Brown’s case, mistakes abound, while Carr’s book carefully transports us to a New York of yesteryear as if tucking us in a time capsule. And yet both books provide details of their periods and historical references of lives depicted that were real, to provide wonderful, entertaining stories.

Crime stories. Murder mysteries. Their “truths” make them believable. Take Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes. Those stories were not real. Details are muddled to the point they can confuse . . . but we follow chains of clues that, in the end, solve mysterious crimes in a most satisfying way. And if we stop to think, little is revealed about Sherlock so that room was left for another mystery . . . and another . . . and another.

Writers can puff out their chests that the mortar and cement that binds the building blocks of stories are their truths and authenticities. Like masons, skilled writers fill the gaps and cracks in a story with details that hold the moment and scene together. With details and truths and authenticities, (Oh , my!) the writer taps into the reader’s emotions, fears, empathies, and curiosities through mystery, suspense, hope, and more. And let’s not forget what can be learned along the way. Consider the queen of mysteries: Agatha Christie. When it came to killing victims by poison, she was the master. Trained as a chemist, Dame Christie worked in the pharmacy at University College Hospital during the war. Her descriptions and use of poisons are so accurate that doctors through the years, have referred to them to help make diagnoses. That’s truth in writing.

When true-life crimes translate to books, in the hands of skillful writers such as Truman Capote In Cold Blood, the tension is heightened to a greater degree, gripping the reader page-by-page. Thomas Harris’s Silence of the Lambs was the inspired by the exploits of real-life surgeon Alfredo Balli Trevino. Harris interviewed Trevino in jail, gaining insight into how the doctor could chop up his gay lover. Harris’s truths? Masterful! Whose pulse doesn’t quicken at the mention of Hannibal Lechter’s name? Recall Helter Skelter. In it, Bugliosi and Gentry chronicle the harrowing Manson massacre with truths that suck the reader into the spiraling vortex of this devastating story. We live it. We are traumatized by it. Details and truths.

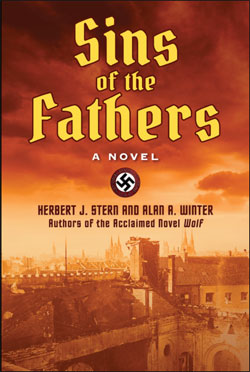

But wait! What if the history that stories are based on is wrong? If the historical record is inaccurate, can we still write compelling mysteries and dramas? The short answer is “yes.” Good writers will make it work. But––and here is where I throw the gauntlet down––I submit that we are entering an era where perhaps, just perhaps, crime, mystery, and suspense writers may consider taking their “truths” to the next level. Before describing what my co-author, Herb Stern and I have attempted to do in Wolf and Sins of the Fathers, let me give you a classic example of fiction superseding historical facts.

Perhaps the greatest crime story of all, one that challenged a long-standing, historical belief thought accurate, was written by Jacqueline Tey in 1951: “The Daughter of Time.” In it, Alan Grant, a detective, convalesces in a hospital bed from a broken leg. He prides himself at being able to “read a person’s character” from their portrait. Bored, a friend brings pictures of historical characters for him to “analyze.” He is intrigued by the image of King Richard III. Through brilliant analysis, Tey’s character not only proves that King Richard III could not have killed his nephews as legend would have us believe, but this book changed the historiography of these events. In other words, fiction set the truth free.

To put our stories (Wolf and Sins of the Fathers) in perspective, let’s return to that yellow brick road of truth. Dorothy found the Wizard behind a curtain that no one had the temerity to “pull back” until she came along. Once she did, the mysteries were over, and the myths and phony truths about the Wizard were exposed. Historians have perpetuated a similar obfuscation by keeping the myths and secrets about Adolf Hitler behind musty curtains for more than a century. Think of the ramifications: historians have censored history! Our challenge: how to reveal these truths? What better way than through fiction!

“Fiction,” as described by Jessamyn West, “reveals truth that reality obscures.” Neil Gaiman, the multi-talented author that crosses many genres, echoed, “We writers have an obligation to write true things . . .,” especially “. . . when we are creating tales of people who do not exist in places that never were—to understand that truth is not in what happens but what it tells us about who we are.” Pointedly, Gaiman states that “fiction is the lie that tells the truth.”

Five years ago, Herb Stern and I chose to challenge myths about Hitler perpetuated by history books that have been accepted the world over without question: Hitler was temporarily blinded during a gas attack. Hitler was asocial. Hitler was incapable of making a friend. Hitler’s proclivities ranged from being asexual to homosexual to neuter to that he suffered from coprophilia (being sexually aroused watching someone defecate or seeing feces). These myths are just that: myths. If they were meant to help identify the next tyrant before disaster befalls a people, they wouldn’t . . . because each is false. Wrong. Untrue. And yet these descriptions continue to find their way into the most recent biographies on Adolf Hitler.

How to best tell these truths when neither of us are a journalist or historian? The answer was to create a character that would be the eyes and ears of the reader via a soldier who had become an amnesiac. This man had no past memory. No family. Knew no one; no one came for him. He befriended the soldier in the next bed to his in the mental ward: Adolf Hitler. In time, our protagonist became a fly on the wall as Hitler and the Nazi Party grew in strength until the day President von Hindenburg asked the Little Corporal to become chancellor.

An aching question: why do books portray Hitler as a screaming gargoyle, a cartoon-like character with bulging, sinister eyes as the world’s greatest mass murder? The answer may be no more complicated than that no historian wanted to write or be accused of giving Hitler human traits. After all, how can such a villain, a fiend, a tyrant, a cruel dictator be anything other than as historians describe Hitler? That he was a black hole? A non-person incapable of human interactions? Cutting Hitler from the herd of human beings makes it easier for the rest of humanity to process what occurred during the Holocaust.

Here is where Wolf and Sins of the Fathers differ from all other books about Hitler: Hitler was a man, portrayed with warts and all. It is true that Adolf Hitler was in a mental institution at the end of World War I; that he was treated by a psychiatrist and not an ophthalmologist; that he did love women and children; and that he had close friends to whom he was loyal to the very end. That he was learned. Cultured. Well-read. He had impeccable manners. And like Steve Berry who uses his Author’s Notes to separate fact from fiction (The Kaiser’s Web is his latest example), we posted our detailed research on www.NotesOnWolf.com. With the soon-to-be-published Sins of the Fathers, Skyhorse Publishing agreed to include our research in the book.

Given the world’s twenty-four-hour news cycle, the rumor mills, the fact that educational bodies are not only revising history but removing key elements from textbooks and forbidding teachers to teach certain “truths,” the role that fiction plays in telling “truths” in all genres of writing is more important than ever.

In 2017, Peggy Noonan wrote in the Wall Street Journal that given the “need for more truth in politics . . .” it was her hope for “more truth in art and entertainment, too.” Noonan went on to discuss the difference between dramatic license and historical truth, the latter of which is necessary to be both respectful to real human beings depicted in the arts as well as to history itself. Otherwise, history will be stretched, clipped, and altered to the point of irrelevance.

Why does this matter? Because, as Noonan says, “we are losing history.” When it comes to movies—and I add books—they have unwittingly caused us to lose history by taking literary license to a point that the reader believes these to be the new “truths.” Without a more solid foundation, today’s viewers get their history lessons from movies and biopics, not textbooks. And that’s where writers can a assume a greater role in the “truths” they portray. Authors may need to take a bit more time, do a bit more research and be a bit more accurate when we use historical events and actual crimes/mysteries to shape our stories. Who ever thought that fiction writers could be the last bastion of truth?

After the curtain had been lifted, the Wizard gave the Scarecrow, Lion, and Tin Man a scroll, a medal, and a clock respectively. Ordinary objects. He assured Dorothy’s friends that they were as “accomplished” as anyone “back where I came from.” But this wizard was a fraud. A bully. A dictator, if you will. If the curtain behind him remained down, he was the feared Wizard with no redeeming qualities. Sound familiar? L. Frank Baum could have been writing about Adolf Hitler, but having published his story in 1900, that stretches the notion of a writer being prescient. But he was. He understood the human spirit.

Another lesson that Baum wanted us to learn is that no matter the bully, no matter what terror lurked behind that curtain, nothing would change until that curtain was pulled back. Likewise, Wolf and Sins of the Fathers drove to pull back that curtain to bare truths and debunk myths about the evilest person of the twentieth century and perhaps of all time Adolf Hitler. And it is these greater truths that crime, mystery, and suspense writers need to incorporate when the opportunity arises so that it is no longer about history repeating itself or that history is written by the victors: it is about history not being lost.